Remembering Professor Peter Gow (1958-2021)

The Department of Social Anthropology and the Centre for Amerindian and Latin American Studies of the University of St Andrews are hosting an international event in remembrance of Professor Peter Gow (1958-2021) with tributes made by colleagues, collaborators and friends. The event is convened by Cecilia McCallum (Federal University of Bahia/ University of St Andrews) and Christos Lynteris (University of St Andrews)

Speakers (in Alphabetical Order):

Giovanna Bacchiddu (Center for Intercultural and Indigenous Research/ Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile)

Françoise Barbira-Freedman (University of Cambridge)

Ben Campbell (University of Durham)

Elizabeth Ewart (Oxford University)

Paolo Fortis (University of Durham)

Stephen Hugh-Jones (University of Cambridge)

Margherita Margiotti (The British Psychoanalytic Council)

George Mentore (University of Virginia)

Juan Pablo Sarmiento Barletti (Center for International Forestry Research/ University of Sussex)

Edward Simpson (SOAS)

Courtney Stafford-Walter (University of Edinburgh)

Christina Toren (University of St Andrews)

Aparecida Vilaça (Federal University of Rio de Janeiro)

Eduardo Viveiros de Castro (National Museum of Brazil/ Federal University of Rio de Janeiro)

Peter Wade (University of Manchester)

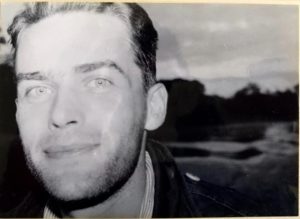

Peter George Gow (1958-2021)

Born in Edinburgh, where he enjoyed a happy childhood, as a young man Pete Gow went to Cambridge to study Social Anthropology. He carried with him a fertile imagination, a sharp intelligence and a wealth of knowledge about the native peoples of North and South America. As a teenager he sought out books about them and began to accumulate a personal library that came to include an extensive collection on Amazonian peoples. Yet his curiosity and enquiring mind led him in other directions too. Gifted with an excellent memory, he happily discussed a wide range of topics, from recent work in primatology or ethology, to the contemporary art scene, punk rock, Scottish kinship, the social history of Dundee or Amazonian cooking recipes. In any conversation with him, one immediately encountered that defining characteristic of his mind, a capacity to see connections that others had not seen, then make them seem both obvious and fascinating. He opened new roads to thought, he was a pathbreaker.

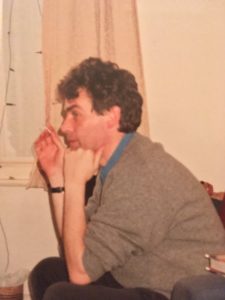

Pete Gow did not know how to be boring. A master of words, written or spoken, his clarity of expression and sometimes wicked sense of humour animated conversations with him. Loved by his students, to whom he was always generous with his time and hospitality, he enjoyed their company and the intellectual engagement they afforded him. Not just a speaker, also an attentive and creative listener, he delighted in talking with friends and strangers from all walks of life: Anthony the homeless man on the streets of Manchester, his Yine comadre, colleagues young and old, a friend’s’ mother, his local shopkeeper – he engaged equally with all. He amazed children and they adored him. His ability to name and recognize other people’s wisdom opened doors for his interlocutors, surprising and allowing them to know and value themselves (and others) in new ways. In this sense, too, he was a pathbreaker.

All these gifts came together in Pete Gow’s distinguished career as an anthropologist, shaped above all by his lifelong relationship with the Yine (Piro) people of Peruvian Amazonia. In 1980 he went there to do extended fieldwork, for his doctoral research. There he lived in Santa Clara village on the Bajo Urubamba river, in a community of ‘Native People’ that was home to Yine families with whom he became close. After completing his PhD at the LSE, under the supervision of Joanna Overing, he went on to teach at the Universities of East Anglia, Manchester, and the LSE, before returning to Scotland. Over a decade during this period, he published two ground-breaking books: Of Mixed Blood: Kinship and History in Western Amazonia (1991); and An Amazonian Myth and its History (2001); and over a dozen articles and book chapters. Much in demand as a speaker, he delivered lectures and conference papers on both sides of the Atlantic. The first book brought the Yine lived world to vivid life in a reorientation of anthropological understanding of kinship away from a focus on ‘blood ties’ and genealogy, to an exploration of how kinship is created temporally as history, out of experience and the memories of the experience of care. As it did so, it elegantly overturned then current approaches to ‘acculturation’ or to ‘inter-ethnic’ relations in the literature. The second book, an extraordinarily original analysis of the history of transformations of a myth in relation to its changing historical context, was made possible by his break-through insight with the Yine: that peoples are not ‘acculturated’ and thus impoverished. Rather, the Yine are merely caught up in, produced by and actively produce long-term historical processes, as indeed are all Amazonians. Recently a translation of his first book was published in Peru as De sangre mezclada: Parentesco e historia en la Amazonía peruana (2020). He was working on the manuscript of a new book when he died.

From the start of his career, Pete Gow maintained close ties with colleagues and friends in South America, especially in Brazil. Between 1996 and 1997 he taught as a visiting professor at the graduate school of the ‘Museu Nacional’ of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. During his time there he engaged intensively with colleagues and students, in dialogues, partnerships and friendships that endured over the following decades. He also published in Portuguese and in Spanish. Thus, his work had repercussions beyond the confines of English-speaking anthropology.

In 2003 he became a professor in the Anthropology Department at the University of St-Andrews and became a core member of CAS, the Centre for Amerindian Studies (then directed by Joanna Overing). His return to Scotland was a source of immense pride and pleasure to him. For the next fifteen years he dedicated himself to teaching and writing, with occasional visits back to South America. Until his retirement in 2017 he provided much inspiration to undergraduates; indeed, many decided to study anthropology after hearing him lecture. For graduate students and colleagues, there will be no replacement for Pete; no substitute for his understanding of indigenous worlds, always in ebullient evolution, never static, expressed through constant interrogation of what was supposedly given in the light of fresh readings of the words and styles of particular Amerindians, through listening yet again to the messages that dialogue, co-experience and then ethnography can convey, and then making sense of it in the here and now. It is hearing Pete do this, effortlessly, with verve and humour, that we will miss. We will miss it too, that is, for there is so much more that we have lost, with his tragic and untimely passing.

Cecilia McCallum

Friend, Colleague and Comadre